ROBERT GARDINER

Royal Northern College of Music, United Kingdom

May 2020

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 19 (1): 54–80 [pdf]

https://doi.org/10.22176/act19.1.54

In the face of increasing teacher burnout, in this paper I explore the theoretical implications of political accountability measures on student music teacher self-efficacy in England. I propose a necessary shift from institutional priorities to weaker personal aspirations as a route towards more sustainable teaching. Through reflecting on my own professional practice, I highlight distinctions between teachers’ individual aspirations and professional action but propose that teachers themselves are somewhat complicit in this disparity. This assertion draws on a Žižekian conceptualization whereby actions aim to appease a fantasy of how the subject perceives they appear to others. For student teachers, I suggest that the attempt to appease their multiple influential figures effectively self-silences personal aspirations; however, given the multifaceted priorities of these influential persons, I argue this appeasement entails a perpetually unfulfilling endeavour. Rather, I call for an intervention which highlights that this desire to appease others and be recognised as proficient is personally sustained, and thus malleable, in order to encourage student teachers to nurture more individually fulfilling and sustainable professional practice.

Keywords: self-efficacy, burnout, student teacher, teacher education, Žižek, educational values

A Call for Weak Education

“Am I where I’m meant to be?” is a typical question posed to me by graduate student teachers, and for me this question epitomises certain dominant epistemologies within education. Here, effective development may be gauged by the extent to which it fits within clear and linear objectives towards expected, and therefore secure, outcomes (Biesta 2009, Allsup 2016). Within a neo-liberal setting, this development typically focusses on utilitarian outcomes associated with a capital-focused society (Bates 2018, Mullen 2019). In this context, notions of “the self” become somewhat insignificant within the “the system,” in that education as a system is paramount, while educators and students function rather like enactors or cogs locked in some grander machine. A teacher’s priority becomes that of location, of finding their own and other’s positions within institutionally set parameters. As such, my student teachers’ question is seemingly always preceded by another unspoken question: “where am I”? Meanwhile, recent reports highlight troubling statistics as to the consistent dropout of graduate teachers in England following only short teaching careers (DfE 2018a, 4; NEU 2019), and research suggests this is often connected to professional burnout (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2009, 2010, 2011; Hultell, Melin, and Gustavsson 2013). It is in this sense that, with a slight change in emphasis, I propose that my student teachers’ question should become “where am I?”

It is this subtle distinction that I intend to explore more fully in this theoretical article. In a world of strong politically defined educational language, I call for Biesta’s (2009) “Weakness of Education” and the importance of individual “interpretation [as] a fundamentally open process” (354) over a hegemony of fixed, closed, or “perfect” (354) relations between teaching and learning. My intention is to explore the complicated nature of student teacher educational values, making the case for an intervention which identifies and encourages individual nuance (the I or me in teaching) as the means towards self-efficacy. I explore the complexities of personal educational values through reflecting on both my own and my student teachers’ professional practices, whereby expressions of value often seem deeply at odds with actions. Drawing on Slavoj Žižek’s (2008a) writings on intersubjectivity and fantasy, I then apply a typically Žižekian ideology critique to these observations. Through referring to broader literary discourse, I aim to elucidate the possible relationship between student teachers’ desires and Žižek’s notion of fantasy (2008a), which is understood to be the subject’s impression of themselves based on their perceived status in the eyes of others. I also outline the multifaceted ways in which these fantasies may be influenced and the consequential implications this has for action. From these understandings, I discuss the need to reaffirm the deeply personal and subtle self in student teachers’ fantasy formation over institutional or political priorities. Finally, I consider the professional implications of such resistance for my student teachers and draw on extensive research published within this journal to highlight not only the challenges faced when aiming to change professional habits, but also the ethical and moral imperative to do so. Again, I draw on Žižek to suggest that my students’ affirmations of personal educational values are the very route to realising their autonomy, from which they may be empowered with the self-efficacy to effect change. It is in this sense that I suggest weak education may encourage strong educators.

The Importance of Self-efficacy

Within the English educational context, recent Department for Education reports highlight that since 2010, at least 30 percent of teachers who qualify in England leave the profession within five years (DfE 2018a, 2018b, Table 8) and a recent National Education Union survey (NEU 2019) suggests that 40 percent of teachers expect to leave within the next five years. In terms of teacher recruitment, Initial Teacher Education numbers consistently fall short of governmental targets (DfE 2019a) despite increased bursaries and “golden handshakes” (DfE 2017) and an estimated investment of £38m in advertising since 2010 (Gibb 2018, Busby 2018). The combination of insufficient recruitment and issues to do with retention has meant that overall teacher numbers have recently fallen (DfE 2018a, 4) despite continually increasing pupil numbers (5). Based on these reports, regardless of apparent incentive and opportunity, a career in teaching seems to be perceived with initial disinterest and developing distaste. Why so?

the Trunchbull said … “My idea of a perfect school, Miss Honey, is one that has no children in it at all. One of these days I shall start up a school like that. I think it will be very successful.” (Dahl 1988, 131)

Children’s behaviour is a recurrent theme of major challenge for many teachers (Rogers 2006, Philpott 2007, Paton 2012), and some researchers have acknowledged its implications for emotional exhaustion, which significantly contributes to teacher burnout (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2009, 2011). For Hultell Melin, and Gustavsson (2013), emotional exhaustion is a core dimension of burnout alongside “depersonalization” (76), which denotes a certain detachment of the individual teacher from their work or colleagues. This depersonalization relates to Conway and Rawlings’ (2015) notion of silencing (28), which describes how beginning teachers in particular feel themselves silenced within school micro-politics; neither themselves as individuals nor their personal work is recognised. This concern is also recognised by Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2011) who identify the fundamental need for teachers to feel a sense of belonging through a personal connection between themselves and their school, whereby “they share the prevailing norms and values of the school where they teach” (1036), and without which there is increased desire to leave the profession.

In England, a pertinent example of such depersonalization can be found in increased political pressure towards teacher accountability. This accountability is particularly apparent in the increased presence of the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted 2015), whose focus from the outset has aimed less at enabling individual teachers to improve than “measuring schools against national standards, with public condemnation for those who fail to meet the targets” (Pitts 2000, 170). Such measurement largely focusses on depersonalized data aimed at proving pupil progression, with examination results (National Curriculum Assessments at primary (DfE 2014) and General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) Examinations at secondary (DfE 2019b)) being of particular importance. [1] For instance, it is common practice in English secondary schools to predict children’s final GCSE grades based on literacy and numeracy tests completed at the beginning of secondary school, from which the actual GCSE results five years later may be used to judge, reward, or punish teachers’ “performance related pay” (DfE 2013b). Within music education specifically, the need to prove pupil progress causes problems whereby what is deemed valuable is often attached to somewhat nebulous and immeasurable concepts like social interaction, self-expression, experience, affect, and emotion (Westerlund 2008, Goffin 2014, Allsup 2016). Music education is therefore often at odds with the hegemonic ideology of measurable progression, with music teachers feeling that their art is consequently marginalised (Daubney, Spruce, and Annetts 2019; Heimonen 2008; Adams 2011). As Horsley (2009) puts it, “hierarchical answerability over communicative reason and top-down over bottom-up policymaking … allow the use of music curricula for political ends, to the detriment of curricular integrity and classroom delivery” (6).

Orzolek (2012) expresses a similar sentiment, stating that accountability is generally accepted as “helpful” (3) where positive improvement is intended, but that “too many in the education workforce have not had any say in the policies that have been developed to ‘improve’ education” (4). Consequentially, accountability is typically understood as politically rather than personally motivated, and for Mutch (2012), de-personalised policy leads to deep teacher resistance, disillusionment, and isolation. Lindblad and Goodson (2011) define this process as “de-professionalization” (3), where agency is removed through a process of increased political supervision. In many ways, therefore, diminishing professional agency combined with the marginalisation of music within the curriculum may justifiably result in English music teachers feeling doubly silenced.

Considering music teacher education specifically within this de-personalised and de-professionalised context, it is understood that relying and reflecting on personal practical experience is integral in forming initial professional values (Kenny, Finneran, and Mitchell 2015; Baker 2006). This assertion, however, poses a significant challenge if, as Hsieh (2016) suggests, a strong sense of self-efficacy is based on the identity formed through these various experiences. The issue is, as discussed, in the contrasting (or indeed contradictory) influences for music teachers on which students are expected to build their foundation. This concern is supported by research that highlights the importance of being a musician as part of the developing music teacher identity, but that there are distinctions and often tensions between musician and teacher identities (Conway et al. 2010; Ballantyne, Kerchner, and Aróstegui 2012; Natale-Abramo 2014; Pellegrino 2015). Based on these understandings, self-efficacy in student teachers may be troubled when teaching experiences in schools challenge (rather than support) personal values associated with the musician identity. As also discussed, within the English context, a de-personalised and de-professionalised educational system rooted in “secure” systems of measurement potentially undermines key tenets of music education. I therefore suggest that “music teacher” potentially becomes something of an oxymoron, whereby important notions of what it is to learn music, particularly those values associated with being a musician, may be effectively irreconcilable with current expectations of “the teacher.” For student teachers, I feel that such differing expectations within education pose significant challenges for forming a robust sense of self-efficacy. As such, it is my belief that an intervention is required to radically shift the emphasis of education away from de-personalised institutional expectations and back towards the personal values of those involved: to re-personalise education.

“What do you value?”—A Story of Professional Hypocrisy as the Basis for Intervention

Drawing on academic and political discourse, I have highlighted the deep challenges I perceive for student music teachers within current educational doctrine in England. It seems important now to discuss these challenges, observing the specific complexities of these pressures on music teachers’ practices. These observations may then serve as the impetus for an intervention in which I aim to shift the focus towards more personal notions of educational value. In so doing, I hope to build a stronger sense of self-efficacy for my student teachers.

In September 2017, Martin Fautley was keynote speaker for the Music Mark North-West Teachers’ Conference (Fautley 2017). Fautley consistently advocates pupil and subject centric education models over institutionally defined models of development (Daubney and Fautley 2014, Fautley and Savage 2008, Fautley 2010); during his afternoon seminar, Fautley asked that the delegates at the conference discuss three simple questions pertaining to that theme. His first question was “what do you value in a musical education?” Re-reading my personal journal, I noted that my own responses included opportunities to explore, finding oneself musically, self-improvement, musical experience, opportunity to grow, togetherness, ensemble, practical involvement, aesthetic worth, artistic integrity/authenticity, and community. After having shared our responses with each other, Fautley then asked, “does anybody disagree with what someone else has said?” Despite the delegates being varied (i.e. employment settings, age, nationality etc.), there was a remarkable consensus within the room. Fautley then posed his third question: “do we practise what we value?” To this question there was a palpable tension in acknowledgement of an uncomfortable truth: no, we typically do not. This discomfort was apparent in the various excuses that followed: “we would like to, but (this) or (that) won’t let us.” Personally, the question became an uncomfortable mirror, connected to tensions existing within my own professional practice and reaffirming the issues described previously: that sense of being silenced by institutional pressures determining how and what I should teach.

Consequently, Fautley’s simple questions functioned as a powerful intervention within my own professional practice by illuminating the dilemma more clearly: my expressions of value are often at odds with my practice. With this revelation came personal reflection on professional choices and actions and an acknowledgement of a certain hypocrisy. While I acknowledge institutional and political pressures (and recognise that there is little I can do to change them), much of my professional practice is self-determined: I choose to teach the way I do. Fautley’s intervention put the spotlight on me, highlighting that I can and should choose to teach what I value. This realisation enabled a stronger sense of my own self-efficacy and encouraged me to pursue small (but important) changes.

For these reasons, I applied Fautley’s intervention to my cohort of student teachers, hoping that the identification and sharing of personal educational values might prompt them to teach in accordance with those very values and concurrently build their professional self-efficacy. I also thought it important to explore where and why these pedagogical choices may be challenged in practice and to discuss the potential limitations of their professional autonomy. I therefore presented Fautley’s questions and, much as with the professional educators, there was a remarkable consensus in valuing many of the nuanced qualities of music (pleasure, creativity, practical experience, self-expression, community, and so forth). Thus far having little practical teaching experience, I changed the subsequent question (“do you practise what you value?”) to “what might get in the way of you teaching these things?” from which resulted an interesting turn of phrase: “there are boxes to tick.” When prompted, my students posed an intriguing list of the perceived pressures and influences on student teachers whilst on teaching placements.

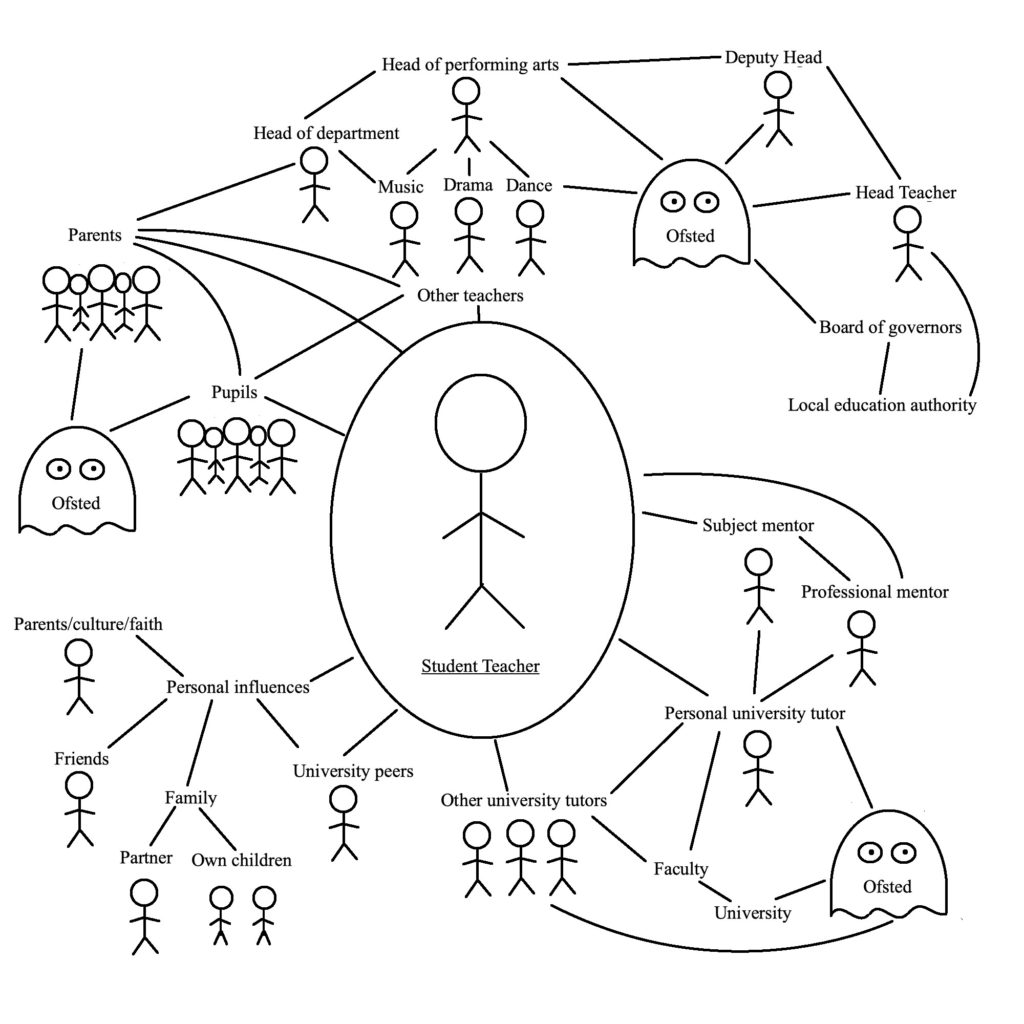

Figure 1 represents typical responses, highlighting the complex interplay between people and institutions and how each is both influencing and influenced. Indeed, connections become significantly more complex in that influential figures typically hold multiple roles (e.g. that the student’s subject mentor might also be the head of department, governor of a local primary school, and a parent) and that student teachers also occupy multiple places between multiple influences. Significantly, the most pertinent influences seemed always to be manifest in people rather than policy: who is influencing the students rather than what. My students seemed less concerned with bureaucratic white paper (e.g. the National Curriculum for Music (DfE 2013a) or a specific exam syllabus) than with keeping people happy. In this respect, Ofsted became those faceless people who come to judge teachers (thus the multiple ghosts in the diagram) rather than a set of practices, values, and policies (Ofsted 2015). Herein lies a significant challenge: where influences are deemed unhelpful or harmful, resistance to those influences may well mean defying the people with whom my students work closely.

Another interesting observation was that, within our discussion, the student teachers directly connected all these people to themselves. If the Head Teacher, Local Education Authority, or Head of Department (etc.) chose to adopt specific strategies, these would all impact directly upon the students’ teaching choices. Working out whose voice is most important therefore becomes virtually impossible, given that each teaching situation may involve a different audience. For example, when the university tutor observed the student teachers, the tick boxes were different from those in the lesson when the students were alone (terrified the class will smell fear and riot). As such, there is a deeply multi-faceted (or indeed multi-faced) nature to the influences within a student’s teaching practice, in whose various gazes the student necessarily changes.

From this assertion, I reaffirm the intention of the intervention. Through identifying personal educational values and the potential challenges in their realisation, I aimed to illuminate these possible tensions for my students rather than solve them outright. That student teachers must adapt practice creatively depending on context is a fundamental facet of and important skill in professional life (Abramo and Reynolds 2015). What was important to me is that, through this dialogical process, my students might develop the capacity to keep reflecting on professional choices and acknowledge where these are at odds with personal values, from which the justification to resist those influences that silence the self may be found. Furthermore, I hoped that they might also recognise that these influences are often manifest in people rather than policy, in order that dialogue may be encouraged—that students might recognise that they are both influential and influenced. Through this re-centring of professional autonomy, I propose that student teachers might build a firm and enduring sense of self-efficacy. In the following section, I discuss in detail the actual implications of this intervention, adopting a Žižekian ideology critique to unpick the complex and confusing nature of student teacher self-efficacy.

Žižek’s Perverts: Enjoying the Oppression

Winston’s greatest pleasure in life was in his work. Most of it was tedious routine, but included in it were also jobs so difficult and intricate that you could lose yourself in them as in the depths of a mathematical problem—delicate pieces of forgery in which you had nothing to guide you except your knowledge of the principles of Ingsoc and your estimate of what the party wanted you to say. Winston was good at this kind of thing. (Orwell 1949, 46)

Within Orwell’s classic Nineteen Eighty-Four, an uncomfortable truth can be found trickling throughout the narrative that, despite outward attempts towards resistance, Winston was complicit in his own oppression. He enjoyed his capacity to enable the Party to commit intricate forgeries that further denied individual freedom, and with his final thought admitted that “He loved Big Brother” (311). As a teenage reader, I found this conclusion terribly disappointing, but now find it to be inescapably apt. Why the change of heart?

Through my strategic intervention, I had hoped for a re-centring of personal values within my students’ pedagogic choices and the consequential resistance to external influences that do not support musical aspirations. I assumed that “ticking other people’s boxes,” though often unavoidable, functions as a hindrance to personal professional intentions. I now believe this assumption to be somewhat unfounded. Rather, in the subsequent weeks, when the students were in teaching placements, I observed a general theme of wilful subjugation, with students seemingly keen to tick others’ boxes. There seemed to be an amazing reverence for aspects of teaching that had not appeared in previous expressions of value, including things like assessment, discipline, and control. These new expressions of value were directly connected to the people of influence within this new context, being most apparent in students’ discussions about their mentors whose methods, practices, and values would be wholeheartedly adopted (whether or not they fit with previous personal aspirations). Within these situations, the previously described tensions between teacher and musician eased, the musician often having been effectively self-silenced.

In truth, I, too, am complicit in this behaviour. When I observe students, my appraisal of them is directly connected to the Teachers’ Standards (DfE 2011) which are used to justify (or not) the awarding of Qualified Teacher Status (QTS). While these standards themselves are by no means detrimental, I am very aware of how I use them to justify my own efficacy and therefore function in the same way as my students. Sitting in the ivory towers of university, I express the importance of individual nuance, while in school observations I attach my students (and by consequence myself) to fixed notions of “teacher” in order to meet the expectations (tick boxes) of my own pressures (i.e. university policy/colleagues, school mentors, Ofsted). I am reluctant to express nuanced personal expressions of value within these contexts, concerned that they may not be perceived as robust. I, too, wilfully self-silence personal values.

In light of this personal revelation, I turn to the theories of Slavoj Žižek to pose a possible explanation. For Žižek (2008a), this wilful subjugation and deference to authority is directly connected to subjective projections of fantasy and relates to early Lacanian notions of “intersubjectivity” (8). Žižek associates this fantasy (who I might be or become) directly with desire and suggests that what is desired is largely defined by what the subject perceives or fantasises others to desire from them. For example, a young boy might want to throw a ball further, but the true desire is not located in a solely personal aspiration; it is fundamentally influenced by how the boy perceives others might regard this act (i.e., his friend being impressed or his father offering praise). Therefore, our desires are not introspective but respond to our perception of the multi-faceted desires of the many “others” around us. As Žižek puts it, “the original question of desire is not directly ‘What do I want?’ but ‘What do others want from me? What do they see in me? What am I to others?’” (Žižek 2008a, 9).

This Žižekian conceptualisation, that the fantasy of “who I might become” is fuelled by the desire to realise “what others want from me,” may therefore offer a helpful insight into the student teachers’ behaviours. Within the complexities of institutional relationships in school (as in the “Student teacher web,” Figure 1), where there are so many perceived strong influences, it is understandable that the students’ aspirations are significantly structured by the institutional discourses and priorities associated with those strong influences. Furthermore, considering again previous assertions that students connect these influences to the people with whom they work (over faceless policy), Žižek’s notion that fantasy is based on the perceived desires that other people have for us is upheld. Concurrently, when in school, those weaker notions of music education (e.g., individual nuance, creativity, self-expression) that were expressed by the students as personal values while in university are now somewhat distant, as there is significantly less contact with the peers and tutors who might also be seen to value these traits. I therefore suggest that these “personal values” are also a fantasy that is simply aimed at a different (and now distant) setting or audience, and it is only natural that these become increasingly silenced within the school setting.

It is important here to consider that strong institutional and weak personal function as two manifestations of fantasy among countless others, and that they are not mutually exclusive. For example, teaching Popular Music in schools may appease a personal aspiration to enable children to “express themselves” whilst simultaneously meeting institutional requirements to enable children to “learn a musical instrument” (DfE 2013a, 1); however, I suggest that Žižek’s conceptualisation offers a useful model that might clearly explain why expressions of value seem to be at odds with practice. Indeed, Žižek argues that it is very much in this practice, in the doing, that desire is most apparent (Žižek 2008b, 28). Where there is personal conflict (this potential tension between musician and teacher), or to use Festinger’s (1962) term cognitive dissonance, weaker aspirations that seem less likely to be gratified naturally become effectively and wilfully silenced in practice.

Discussion: The Dangers of Subjugation and “Yossarian” Salvation

Drawing on this conclusion, I suggest that there may be serious, and indeed dangerous, implications resulting from this wilful silencing of personal aspirations. In a typically Žižekian way, I draw here on literary analogies for illustration and critique. In East of Eden, Steinbeck (1952/2017) introduced us to the character of Cyrus, who, during his short period of service in the American Civil War, spent his time drinking, gambling, and whoring, only to have his leg shot and amputated in his first and only piece of active service. To build his prestige, he subsequently built an extraordinary reverential fantasy about the army and his exemplary discipline and highly influential action in the war. Describing the army, he stated:

They’ll first strip off your clothes, but they’ll go deeper than that. They’ll shuck off any little dignity you have—You’ll lose what you think of as your decent right to live and to be let alone to live. They’ll make you live and eat and sleep and shit close to other men. And when they dress you up again you’ll not be able to tell yourself from the others. You can’t even wear a scrap or pin a note on your breast to say, “This is me—separate from the rest.” (Steinbeck 1952/2017, 33–4)

Upon returning home, Cyrus applied this idealism to his parenthood, becoming lost in his own fantasy; he rejected the two persons of his children and aimed instead at a faceless uniformity of how his children “should be.” In this void of personality, the boys struggled to realise their father’s intentions, one turning on the other in jealousy, resulting in a contemporary retelling of Cain and Abel.

The second analogy comes from Stanley Kubrick’s (1987) cult classic, Full Metal Jacket. The first section of the film presented this “boot-camp” depersonalisation, where everything becomes automated and machine-like under the tyrannical Drill Sergeant. The film focussed on a conscript (Pvt. Leonard “Gomer Pyle” Lawrence) who fully and wilfully submitted to this system and initially exceled, but eventually failed to realise the fantasy of becoming a perfectly uniform and mindless soldier. The finale of the first section of the film concluded with Pvt. Lawrence shooting his drill sergeant and himself. In his commentary on the film, Žižek stated: “If you get too close to it, if you over identify with it, if you really, immediately become the voice of this superego, it’s self-destructive. You kill people around you, you end up killing yourself” (Žižek and Fiennes 2012, timestamp 1:23–4).

In both analogies, the absolute wilful subjugation of the personal ends up building a fantasy that is eternally unmanageable: to perfectly realise an institutional desire. No one could ever succeed in this respect (there is no perfect soldier/son/teacher), but in denying the personal, there is no space in which to excuse or resist the failure (of, for example, personal weakness, character, aspiration). Returning to the student teachers, the consequence of trying to perfectly appease the strong and definite institutional expectations of the school must always amount to a certain failure, particularly in music where pedagogy and practices seem often to be at odds with the expectations. I would argue that, based on these two analogies, the consequence of trying to do so may manifest in a certain self-destruction or burnout.

Within Kubrick’s same narrative, however, another soldier (Pvt. J. T. “Joker” Davis) provided an avenue of hope. Pvt. Davis was determinedly human throughout the boot-camp process, and it is through him that the situation seemed darkly comical. In him there is a recognition of both the self and the institution, and an acceptance (to an extent) of the necessary “circus” of boot-camp: I need this to survive the war, but I am not this. As such, Pvt. Davis’ fantasy is still deeply connected to personal aspirations, and in this balance, he finds confidence and self-efficacy.

Having previously alluded to Winston’s dystopian world of complicit oppression and false resistance, I turn to my final literary reference, which is one of successful resistance and independence. In Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1955/2010), Yossarian remained perfectly and comically rational throughout the atrocious ordeal of being a World War II bomber pilot. In this setting, Yossarian balanced fantasy between institutional and personal aspirations. He was aware he must comply to please his supervisors (and keep his job flying the plane, not trusting someone else to do it) while simultaneously, he was keenly focussed on personal aspirations (staying alive). He employed constant evasive manoeuvres and dropped his bombs at the first possible moment, regardless of proximity to the target. This personal awareness was explicitly put in one dialogue with a colleague:

“They’re trying to kill me,” Yossarian told him calmly.

“No one’s trying to kill you,” Clevinger cried.

“Then why are they shooting at me?” Yossarian asked.

“They’re shooting at everyone,” Clevinger answered. “They’re trying to kill everyone.” (Heller 1955/2010, 19)

In this way, Yossarian did not allow himself to be subsumed into the institutional fantasy of “American soldier in war” found in the expectations of the other soldiers but affirmed himself as individually autonomous (with personal aspirations) until his eventual escape to freedom.

Applying these examples and theorisations to educational contexts allows for a different dynamic within the previously discussed challenges in student teachers’ fantasy formation. Within these final analogies, there was a recognition by Pvt. Davies and Yossarian of both personal and institutional desires, in the balance of which a strong sense of self-efficacy and confidence is formed in order that they may autonomously act. As F. Scott Fitzgerald (1936) put it, “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function” (41). Applying this notion specifically to student teachers and the dangers I perceive in silencing personal aspirations in order to appease institutional desires, I think it is important to recognise those desires as both inevitable and, to a certain extent, helpful. Fitting in with the structures of the school is an essential component of being a schoolteacher, giving a certain amount of security, purpose, belonging, and consistency to a teacher’s practice, to the benefit of both the teacher and their pupils; however, it is in the recognition of this desire to appease school structures, and in particular to appease people associated with those structures, that I suggest student teachers may find a certain clarity from which they may negotiate practice to more healthily include personal desires. Key to this process is the assertion that such desires draw on a fantasy which is always subjectively sustained, and thus I argue, is also personally malleable. Through highlighting the “connection between recognition of desire and desire for recognition” (Žižek 2008a, 8), I hope that, at certain moments, student teachers may feel empowered to resist the silencing of personal aspirations towards a more healthy pedagogical balance. In this very process of recognising our desire to appease others and decidedly affirming ourselves as autonomous within that process, I suggest we might build a stronger sense of self-efficacy.

Application: The Challenge and Moral Imperative of Resistance

It is very tempting for me to leave it at that, suggesting something of a philosophical answer to certain problems I perceive in education in England, but the principal problem I foresee therein is a necessary acknowledgement that this solution is always only my perspective. In the privileged position as a university teacher, my perspective is necessarily positioned in a particular way. Despite the fact that I continue to work weekly as a music teacher in primary and secondary schools, my years of experience as an educator and my secure position within Higher Education afford me the time, confidence, and (I would suggest) authority to criticise practice in a way that may be lacking in student teachers. In other words, my affirmation of how students might behave is always already framed by my own understandings, such that I necessarily see the students’ perspective through the eyes of an experienced and privileged teacher. Drawing on Cole’s (1996) notion of prolepsis, a just criticism of my previous conclusion is that I “presuppose that the [students] understand what it is that I am trying to teach as a precondition for creating that understanding” (183). Talbot (2013) thus suggests that teachers, “forge future projections based on their own past cultural histories and experiences, often assuming that what worked for their past experiences and contexts will apply to their students’ current experiences and contexts” (67). Within the final section of this article, I therefore aim to step out of my own situational experience and draw on research published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education (ACT) that highlights some of the broader challenges and philosophical implications that must be considered when aiming to resist current educational practices. I then aim to reaffirm the moral and ethical imperative of such resistance to present a pragmatic account of how this may be realised, once again drawing on a Žižekian conceptualisation of the subject and their position within society as a possible route to stronger student teacher autonomy.

Within ACT, a consistent theme that arises when questioning teaching practice is that of “habit” (e.g. Goble .2005; Bowman 2005; Regelski 2016, 2011). As described previously, fitting in with the habitual practices and structures of a school (e.g. from taking the class register through to fulfilling the requirements of the curriculum) is a fundamental aspect of being a teacher. For Mantie and Talbot (2015), such “habits … are essentially a good thing” (129) in that they “help create stability, allowing society to function smoothly” (129). For Regelski (2009), the habits and practices within a given context connect to Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, which denotes the way in which such practices are governed by the cultural and social values of “a particular society, region, or community” (67). Here, Regelski suggests that music education is a “field” (68) that competes with other fields within a given context or “world” (68) and that music education’s position connects to the way that it is deemed “relevant or valuable” (68). The issue here is that “when habits of praxis do not arise as ‘common’ (shared) or widespread and important, the praxis in question is threatened with extinction” (69). Therefore, Regelski argues that “institutions only function given their Background conditions” (2013, 8) and the way they meet a practical need, fit within a collective societal intentionality, and submit to the constitutive rules of that society (7). In essence, what is suggested here is that the purpose and habits of schools (among other institutions) are always already predefined by their societal context.

At a subjective level, Mantie and Talbot (2015) therefore suggest that the teacher’s very capacity “to ‘rationally’ choose between alternatives is hardly an unproblematic matter of agency because we are born into an existing structure of values” (129). Therefore, “the efforts to critique (let alone change!) the habits of the status quo are enormously difficult” (129–30). This challenge is exacerbated by Määttänen’s (2005) assertion that “habits of actions are repeatedly defined and treated as beliefs” (3) such that there is always “linkage between rationality and habituality” (Bowman 2005, 2). In other words, habitual actions as regulated by a societal context can be understood, from this perspective, to actively shape beliefs and values. This stance largely aligns with the Foucauldian post-structuralist notion of discourse and the way that historical, social, and cultural contexts always have a certain power over subjective understandings, positioning, and values (Foucault 2002). As such, Hess and Talbot (2019) argue that “through the concept of habitus, field and capital … the education system preserves existing social hierarchies” (94) through a process of reproduction in which “the agent is considered to be mostly unaware of how structural forces influence conduct” (95). Regelski (2013) mirrors this claim with his suggestion that there is a tendency towards “taken-for-granted default positions” which “can lead to problems, especially for those unaware of what the default settings are that they rely upon mindlessly … and who thus proceed to employ them unaware of or unconcerned with their built-in biases and limitations” (8-9). It is against such mindlessness that Hess and Talbot (2019) suggest that there is an imperative that “education must move beyond a model that rewards docility to an approach that fosters critical thinking” (97) in order to develop “a critical awareness of the dangers of ideological blinders in musical education” (Regelski 2016, 31). In keeping with my previous arguments, I concur with this call to criticality.

The question for me is, how can such criticality be achieved? Where educational values and beliefs are so rooted in contextual experiences, how can student teachers themselves possibly recognise (from their subjective perspective) that certain habits are detrimental and thus require changing? Where there is a lack of awareness as to how structural forces influence practice and values, Eagleton (1991) asks, “how would they ever come to embark on this process [of change]? For there is nothing in their conditions now which provides the slightest motivation for it” (214). I therefore suggest that it might be pertinent to depart from this philosophical perspective and return once again to Žižek in order to posit a possible solution. While the point here is not to enter into a philosophical discussion about the distinctions between habitus and ideology (i.e. Bourdieu versus Žižek—perhaps another day…), I believe that Žižek’s particular stance opens up certain possibilities that might otherwise be impossible.

Written as a critical response to post-structuralist theory, Žižek’s Sublime Object of Ideology (2008b) criticises the notion that subjective values and identities are an unwitting product of society. At a fundamental level, Žižek places the subject as an active and knowing agent within the ideological structures of their particular social context. He argues that the subjective illusion is not on the side of knowledge, but that individuals “know very well” (28) the ideological structures that organise their world, but nevertheless act in accordance with them. For example, Žižek highlights the way that society uses money (28) and how everyone knows that the paper notes inside their wallets have no intrinsic value, but through the social act of behaving as though they have value (i.e. exchanging them for physical items), a structure is built that in effect creates a value (albeit false). Or, drawing on a teaching analogy used previously, English music teachers know very well that predicted grades based on literacy and numeracy tests unfairly position students in music lessons, but nevertheless work within those parameters when charting children’s progression. Thus, Žižek states that “they know that, in their activity, they are following an illusion, but still, they are doing it” (30). Therefore, it is in everyday actions (or indeed habits) that ideological structures are perpetuated, and Žižek roots the driver for that process in subjective fantasy: “the fundamental level of ideology … is not that of an illusion masking the real state of things but that of an (unconscious) fantasy structuring our social reality itself” (30). Based on my previous discussions on fantasy, for Žižek the impetus for the perpetuation of socio-cultural structures is in the way that the subject perceives that their actions appease the expectations of those around them. Žižek does not deny that there are pre-existing structures within society, but suggests it is not the structures themselves that regulate behaviours (as in the conventional notion of ideology) but rather the subject’s wilful desire to fit in with those existing structures in order to appease others. The true core of ideology is therefore located in the desire to appease (to be recognised); in my opinion, it is there that the focus of intervention should be directed.

While this conceptualisation implicates the subject themselves in the process of perpetuating ideological structures, there simultaneously appears the very route to resistance and change: that the subject is already autonomous. As discussed previously, where the locus of desire rests in the subject’s fantasy of how they appear to others, I suggest that the subject has a certain control over this process. Firstly, I suggest that the illusion inherent in this notion of fantasy can be dispelled through the process of engaging in specific dialogue with those others in whose eyes the subject seeks recognition. For my students, I concur with Gates’ (2005) suggestion that “individuality … becomes agency, personal as well as social, but only when coupled with communication” (11). Students should communicate with others in order to clarify what is expected of them, but also to affirm what they expect in return. Secondly, where detrimental structures are rooted in everyday actions or habits, I suggest that it is in teaching practice itself that change must manifest; actions might speak louder than words. Here I draw on Regelski’s (2011) distinction between “mindless habits … based on status-quo routines” and “mindful habits … that when past habits are inadequate to the uniquely situated new problems that teachers typically face, a mindful process begins that leads to a new solution” (79). As Bowman (2005) puts it, “to progress is to renounce formerly useful habits for newer, more promising ones” (3). I therefore hold to Hess and Talbot’s (2019) suggestion that “music education offers possibilities to create a narrative towards a different possible future” (105).

Indeed, returning to the educational dilemma presented at the start of this article, I suggest that in the face of increasing teacher dropout in England, there is a moral imperative to enable student teachers to creatively forge new and more healthy professional habits. More broadly, I hope that teacher educators engage in dialogue with their students in order to highlight the possible dangers (for the students themselves, but also the children they teach) in perpetuating the status quo. I use the word dialogue deliberately, because I believe it is through this very process that student teachers may be encouraged to clarify and communicate their own perspective and to recognise it as valid. Indeed, I expect that such dialogue might enable students to criticise the very views of this (privileged) university tutor and move towards a better future pedagogy.

Conclusions: A Call for Intervention

At the outset of this article, I set out to explore the impacts of dominant epistemology found currently within English music education. Initially, I postulated that recent statistics highlighting poor student teacher retention figures may be connected to accountability measures within education in England and how these measures might pressure student teachers to submit to institutional dominances to the detriment or silencing of personal aspirations and values. Instead, I observed a wilful subjugation and apparent aspiration to fulfil those institutional demands. Analysing this apparent contradiction through a Žižekian lens, I attributed this wilful subjugation to subjective desire and how fantasy may be formed through a multifacteted intersubjectivity. I theorised that student teachers’ desire is manifest in how they perceive others to consider them, even if this entails conflicting expressions of value. That there are so many influential others to appease amounts to an inevitable subjugation of the self, such that weaker personal values are adjusted towards stronger institutional ones.

Within this scenario, however, there is a real danger of becoming lost, with my initial question, “where am I” being particularly apt once again. Within the virtually endless (and truly unknowable) fantasised opinions of others, student teachers are naturally incapable of fulfilling these perceived expectations. In the process of trying, I suggest that there comes an increasing awareness of their incapacity to do so and, subsequently, an erosion of self-efficacy leading to emotional exhaustion and the very real possibility of burnout. Rather, it is my simple intention to encourage interventions within student teacher education to awaken students to a realisation of this desire for recognition. In so doing, I feel it is important to acknowledge that navigating the habits and structures of the school is an important part of being a teacher and that there is a certain inevitability in desiring the recognition of others; however, it is the recognition of that desire that situates the self within this process and thus grants a certain autonomy in order to develop a criticality towards those very habits and structures. In so doing, student teachers might seek less the where in “where am I,” which defers themselves to the opinions, structures, and matrices of others, but rather seek the I within those settings. By consequence, students might build a stronger sense of self-efficacy and a more stubborn or resistant professional practice, one that better values and pursues personal musical aspirations.

About the Author

Robert Gardiner is currently employed as Assistant Head of Music Education at the Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester, UK. He completed his Bachelor degree at the RNCM, his PGCE at Manchester Metropolitan University and his Masters at Zurich University of the Arts. Robert is currently completing his Doctorate at Manchester Metropolitan University based on his work in teacher education at the RNCM. He is a professional educator specialising in whole-class music pedagogies and specific instrumental music teaching, designing and implementing diverse music pedagogies in all sectors of primary, secondary and higher education. Current research interests include music teacher education, educational discourse and policy, ideology and education, musical creativity, and social inclusion through music. Whilst working as a full-time educator, Robert has also maintained a professional clarinet playing career in contemporary performance practice.

References

Abramo, Joseph Michael, and Amy Reynolds. 2015. Pedagogical creativity as a framework for music teacher education. Journal of Music Teacher Education 25 (1): 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083714543744

Adams, Jeff. 2011. Editorial: the degradation of the arts in education. IJADE 30 (2): 156–60.

Allsup, Randall Everett. 2016. Remixing the classroom: towards an open philosophy of music Education. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Baker, David. 2006. Life histories of usic service teachers: the past in inductees’ present. British Journal of Music Education 23 (1): 39–50. https://doi.

org/10.1017/S026505170500673X.

Ballantyne, Julie, Jody L. Kerchner, and José Luis Aróstegui. 2012. Developing music teacher identities: an international multi-site study. International Journal of Music Education 30 (3): 211–26. https://doi.org/10.1177

/0255761411433720

Bates, Vincent C. 2018. Faith, hope, and music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 17 (2): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.22

176/act17.2.1

Biesta, Gert J. J. 2009. On the weakness of education. Philosophy of Education Yearbook, 354–62. https://ojs.education.illinois.edu/index.php/pes/

article/view/2728/1056

Bowman, Wayne. 2005. The rationality of action: Pragmatism’s habit concept. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 4 (1).

Busby, Eleanor. 2018. Government falls short of teacher training targets in most secondary school subjects. Independent. (November 29) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/government-teacher-training-targets-recruitment-dfe-secondary-school-shortages-a8659846.html

Cole, Michael. 1996. Cultural psychology: a once and future discipline. Cambridge, MA: The Bellmap Press of Harvard University Press.

Conway, Colleen, John Eros, Kristen Pellegrino, and Chad West. 2010. Instrumental music education students’ perceptions of tensions experienced during their undergraduate degree. Journal of Research in Music Education 58 (3): 260–75.

Conway, Colleen, and Jared Rawlings. 2015. Three beginning music teachers’ understandings and self perceptions of micropolitical literacy. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 204 (Spring): 27–45.

Dahl, Roald. 1988. Matilda. Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd.

Daubney, Alison, and Martin Fautley. 2014. ISM—The national nurriculum for music. Incorporated Society of Musicians. London. https://www.

ism.org/images/files/ISM_A_Framework_for_Curriculum,_Pedagogy_and_Assessment_KS3_Music_WEB.pdf.

Daubney, Alison, Gary Spruce, and Deborah Annetts. 2019. Music education : state of the nation. All-Party Parliamentary Group, The Incorporated Society of Musicians and Sussex University. https://www.ism.org/

images/images/FINAL-State-of-the-Nation-Music-Education-for-email-or-web-2.pdf

Department for Education. 2011. Teachers’ standards. https://www.gov.uk/

government/publications/teachers-standards

Department for Education. 2013a. Music programmes of study: key stage 3 national curriculum in England. https://www.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239088/SECONDARY_national_curriculum_-_Music.pdf

Department for Education. 2013b. New advice to help schools set performance-related pay. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-advice-to-help-schools-set-performance-related-pay.

Department for Education. 2014. National curriculum and assessment from September 2014 : information for schools. https://assets.publishing.

service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/358070/NC_assessment_quals_factsheet_Sept_update.pdf

Department for Education 2017. Bursaries and funding. https://getinto

teaching.education.gov.uk/funding-and-salary/overview

Department for Education. 2018a. School workforce in England: november 2017. London. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/719772/SWFC_MainText.pdf

Department for Education. 2018b. School workforce in England: november 2017 (tables). https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/school-work

force-in-england-november-2017

Department for Education. 2019a. Initial teacher training ( ITT ) census for the academic year 2018 to 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/

government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/759716/ITT_Census_2018_to_2019_main_text.pdf

Department for Education. 2019b. Secondary accountability measures: guide for maintained secondary schools, academies and free schools. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/783865/Secondary_accountability_measures_guidance.pdf

Eagleton, Terry. 1991. Ideology: An introduction. London: Verso.

Fautley, Martin. 2010. Assessment in music education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fautley, Martin. 2017. Music education and its assessment in schools. In Music Mark North West Teachers’ Conference. Preston.

Fautley, Martin, and Jonathan Savage. 2008. Assessment for learning and teaching in secondary schools. Exeter: Learning Matters.

Festinger, Leon. 1962. A theory of cognitive dissonance. London: Tavistock Publications.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. 1936. The crack-Up. Esquire (February 1936). http://classic.esquire.com/the-crack-up/

Foucault, Michel. 2002. Archaeology of knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge classics.

Gates, J Terry. 2005. Dewey, communication, and habitus. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 4 (1): 1–17.

Gibb, Nick. 2018. Teachers: recruitment: Written question—127648. Parliament. (February 21) https://www.parliament.uk/written-questions

-answers-statements/written-question/commons/2018-02-08/127648.

Goble, J. Scott. 2005. On musical and educational habit-taking: Pragmatism, sociology, and music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 4 (1): 1–17.

Goffin, Kris. 2014. Music feels like moods feel. Frontiers in Psychology 5 (Apr): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00327

Heimonen, Marja. 2008. Nurturing towards wisdom: justifying music in the curriculum. Philosophy of Music Education Review 16 (1): 61–78. https://doi.org/10.2979/PME.2008.16.1.61

Heller, Joseph. 2010. Catch-22. London: Vintage books. (Original work published 1955).

Hess, Juliet, and Brent C. Talbot. 2019. Going for broke: A talk to music teachers. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 18 (1): 89–116. https://doi.org/10.22176/act18.1.89.

Horsley, Stephanie. 2009. The politics of public accountability: implications for centralized music education policy development and implementation. Arts Education Policy Review 110 (4): 6–12. https://doi.org/10.

3200/AEPR.110.4.6-13

Hsieh, Betina. 2016. Professional identity formation as a framework in working with preservice secondary teacher candidates. Teacher Education Quarterly 43 (2): 93–112.

Hultell, Daniel, Bo Melin, and J. Petter Gustavsson. 2013. Getting personal with teacher burnout: a longitudinal study on the development of burnout using a person-based approach. Teaching and Teacher Education 32: 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.01.007

Kenny, Ailbhe, Michael Finneran, and Eamonn Mitchell. 2015. Becoming an educator in and through the arts: forming and informing emerging teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education 49: 159–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.004

Kubrick, Stanley. 1987. Full metal jacket. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros.

Lindblad, Sverker, and Ivor Goodson. 2011. Researching the teaching profession under restructuring. In Professional Knowledge and Educational Restructuring in Europe, edited by Ivor Goodson and Sverker Linblad, 1–11. Rotterdam: Sense Publishing.

Määttänen, Pentti. 2005. Classical pragmatism on mind and rationality. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 4 (1): 1–12.

Mantie, Roger, and Brent C. Talbot. 2015. How can we change our habits if we don’t talk about them? Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 14 (1): 128–53.

Moran, Renee M. R. 2017. The impact of a high stakes teacher evaluation system: educator perspectives on accountability. Educational Studies 53 (2): 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2017.1283319.

Mullen, Jess. 2019. Music education for some: music standards at the nexus of neoliberal reforms and neoconservative values. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 18 (1): 44–67. https://doi.org/10.22176/

act18.1.44

Mutch, Carol. 2012. Curriculum change and teacher resistance. Curriculum Matters 8: 1–8.

Natale-Abramo, Melissa. 2014. The construction of instrumental music teacher identity. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 202: 51–69.

National Education Union (NEU). 2019. The state of education: workload. https://neu.org.uk/press-releases/state-education-workload

Ofsted. 2015. The common inspection framework: education , skills and early years. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/

system/uploads/attachment_data/file/717953/The_common_inspection_framework_education_skills_and_early_years-v2.pdf

Orwell, George. 1949. Nineteen eighty-four. London: Penguin.

Orzolek, Douglas C. 2012. The call for accountability. Journal of Music Teacher Education 22 (1): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083712452260

Paton, Graeme. 2012. Bad behaviour in schools ‘fuelled by over-indulgent parents’. The Telegraph. (March 30). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

education/educationnews/9173533/Bad-behaviour-in-schools-fuelled-by-over-indulgent-parents.html.

Pellegrino, Kristen. 2015. Becoming music-making music teachers : connecting music making , identity , wellbeing , and teaching for four student teachers. Research Studies in Music Education 37 (2): 175–94. https://doi.org/

10.1177/1321103X15589336

Philpott, Chris. 2007. The management and organisation of learning in the music classroom. In Learning to teach music in the secondary school, edited by Chris Philpott and Gary Spruce, 102–18. Abingdon: Routledge.

Pitts, Stephanie. 2000. A century of change in music education. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2009. Curriculum reform: reclaiming ‘music’ as social praxis. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 8 (1).

Regelski, Thomas A. 2011. Praxialism and ‘aesthetic this, aesthetic that, aesthetic whatever.’ Action, Criticismm, and Theory for Music Education 10 (2).

Regelski, Thomas A. 2013. Re-setting music education’s ‘default settings.’ Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 12 (1).

Regelski, Thomas A. 2016. Music, music education, and institutional ideology: a praxial philosophy of musical sociality. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (2).

Rogers, Bill. 2006. Classroom behaviour. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. 2009. Does school context matter? Relations with teacher burnout and job satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (3): 518–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.12.006

Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. 2010. Teacher self-efficacy and teacher turnout: a study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (4): 1059–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. 2011. Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (6): 1029–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001.

Steinbeck, John. 2017. East of Eden. London: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1952).

Talbot, Brent C. 2013. The music identity project. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 12 (2): 60–74.

Westerlund, Heidi. 2008. Justifying music education: A view from here-and-now value experience. Philosophy of Music Education Review 16 (1): 79–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/3385206.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2008a. The plague of fantasies. London: Verso.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2008b. The sublime object of ideology. London: Verso.

Žižek, Slavoj, and Sophie Fiennes. 2012. The perverts guide to ideology. New York: Zeitgeist Films.

[1] Primary NCA assessments are completed twice at ages 7 and 11, and secondary GCSE tests are at age 16.